Aloneness has a cousin. Its name is loneliness.

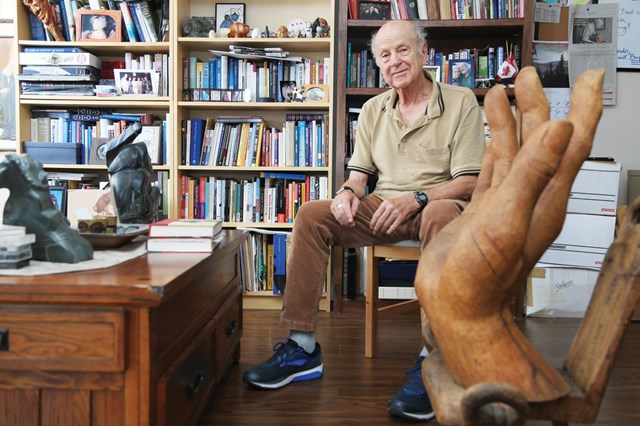

Longtime West Vancouver resident David Kirkpatrick makes sure he always knows the difference between the two, having spent several years alone – and at times, lonely – even though he was still married.

He’s well-versed at navigating such emotionally fraught waters himself, but isn’t confident others married or in a relationship with someone living with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia would be. That’s what prompted him to put out his new book, Neither Married Nor Single.

“I think in an Alzheimer’s or dementia marriage we’re in a no man’s land,” Kirkpatrick tells the North Shore News. “(It’s like) we’re not married, and we’re not single. We’re having conflicts that married people face but they don’t get resolved, they deepen and require patience and I think a certain amount of courage.”

He says that for spouses of dementia or Alzheimer’s patients, it can feel like the relationship is in a perpetual “in-between” stage, stuck in a kind of relationship purgatory, or no man’s land.

“With an Alzheimer’s marriage we’re in a downward path facing conflict, anguish, turmoil, and issues like how do we think about somebody who’s still there, and do we? Do we take on a new partner or not?”

Kirkpatrick’s wife, Clair, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in 2007. The signs had been there for years prior and had reached a headway with brief lapses in memory, disorganization, and general agitation.

One of the hardest moments in their marriage following that initial diagnosis came years later, when Clair, “no longer comfortable within her own home or within her deteriorating sense of self,” Kirkpatrick writes, called the police on her husband because she thought he was an intruder in their own home.

Clair was admitted to a long-term care facility on the North Shore shortly thereafter, in 2010. That’s when Kirkpatrick decided he’d turn the comforting journal entries he’d been writing about Clair and his journey with her Alzheimer’s into a book.

“It helped ease the anguish and grief of losing her because she wasn’t at home anymore, but I was still visiting her every day, or every other day,” he says. “The book helped me log that passage emotionally and geographically.”

And for the would-be reader, he says the purpose is simple: It’s a how-to book for the person in an Alzheimer’s or other dementia marriage.

Kirkpatrick, who practised psychology and psychiatry in both Canada and the U.S. for more than 40 years, says it can be an “emotionally exhausting experience” being in a relationship with someone living with Alzheimer’s, despite how much you might love them.

His best advice, like all good advice, is simple. You have to take it “one day at a time,” he says.

“You don’t do it by yourself, you do it with friends, you do it with fellow caregivers, you do it with support groups, you do it in counselling, if that’s your thing,” he says, adding that it’s important to remember that you’re not alone, even if it might feel like it.

In the midst of an aging population, there is more and more literature on the subject of dementia all the time. In Neither Married Nor Single Kirkpatrick attempts to add to that discourse with an intimate look at two people reckoning with a marriage in flux due to illness, and through addressing questions that, he notes, once seemed off-limits.

“The non-fictional accounts are usually caregivers usually looking after mom or dad, or grandparents. ... But none about the ‘Me and You’ – the actual marriage that we’re facing, that we are losing, or feel like we’re losing,” he says.”

His book also addresses the specter of loneliness that one might feel when their partner with dementia lives in care.

Kirkpatrick explains how after Clair had been in care for several years he looked to enter another relationship, much to the chagrin of some people in his life and the positive encouragement from others.

“We cope with friends and family,” he says. “We cope with learning to have the courage to ask the questions: ‘Is it time to put my partner into a care home? Is it time I started talking to that woman in the coffee shop that I see every day that’s kind of sweet? Or is that appropriate?”

While Kirkpatrick would answer in the affirmative, he argues what’s more important is for the partner in such a situation to gather the courage to ask tough questions and express the experience they’re going through.

“The caregiver groups I was in tiptoed around these issues and did not really give the caregivers permission to even ask the question,” he explains.

“You’re a human being, you have conflicts. ... The caregiver needs the support not just to get the answers but even more to ask the questions.”

After 20 years of marriage, Clair passed away last year. Kirkpatrick reflects fondly on his time with his wife, but notes that it’s OK to be alone. It’s loneliness that needs a remedy.

He hopes his book can be that remedy for those spouses, partners, or individuals in a similar situation. As he notes towards the end of his book: “Finally, remember that there is life for you after your partner’s struggle with Alzheimer’s.”