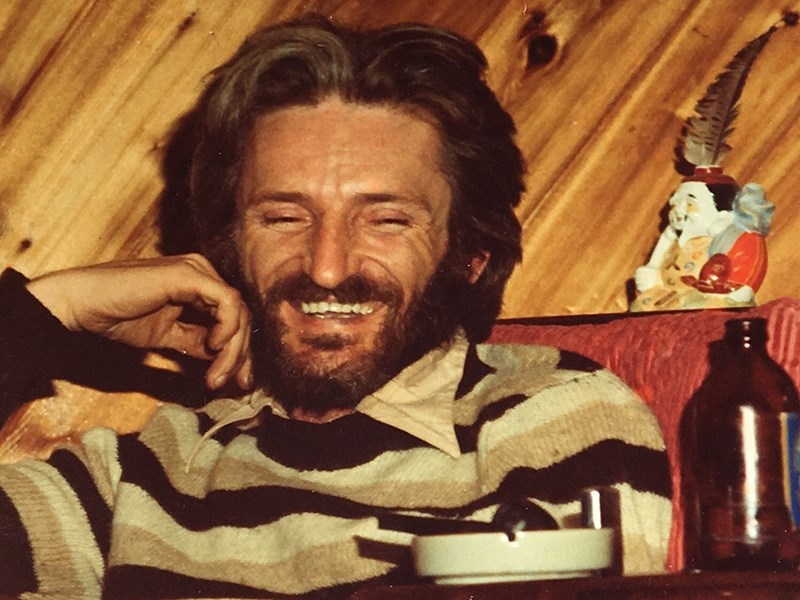

Previous chapter [“The cabin,” May 31]: In the early 1980s, the hermit Russell Letawsky constructed a tiny one-room cabin to live in permanently on the Gifford Peninsula in Desolation Sound. The shack had no running water, electricity or means of communication. The hermit became an influential yin to my conservative father’s yang. Sometimes, he would travel by boat with my family for a visit to Lund, the closest civilization to our cabins. It was at the notorious Lund Pub where Russell would very occasionally find himself in the middle of a bloody bar scrap.

The Lund Pub was the catch-all, dead-end bottleneck at the end of Highway 101 for all those looking to wet their whistle after a long day on the ocean or in the woods. Inside that pub in the 1980s you could find all kinds: loggers, fishermen, clam diggers, bikers, hippies, draft dodgers, oyster farmers, construction workers, members of the Tla’amin Nation, and a scattering of tourists.

When I heard stories about the Lund Pub as a kid, I would picture a cross between an old west saloon, the cantina on Star Wars, and Molly’s Reach from The Beachcombers.

Russell was generally a peacenik and loved socializing in the pub after long stretches of isolation in the Desolation Sound wilderness, but there were often clashes between the blue-collar workers and hippies like Russell.

One time, one particularly huge logger started picking on Russell.

“We were in the pub, and this guy across from me was somehow getting upset with me without knowing me or talking to me or anything,” remembered Letawsky. “He must have been 250 pounds.”

The logger suddenly got up and attacked Russell. Grappling together, the hermit and the logger spilled out onto the deck of the Lund Pub. Somehow, Russell, who maybe weighed 175 pounds wet, managed to get the best of big logger. Russell put him in a tight headlock and held on for dear life.

“I had him over the railing and I wouldn’t let him go,” exclaimed Russell excitedly. “I held on and I squeezed until he promised me that he was not going to fight with me. He promised, so I let him go and I went back inside and sat down. I was talking to these girls I was with when one of them shouted ‘watch out!’ The door swung open and this boot came in and hit me on the chin.”

The steel toe of the logger’s work boot had gouged open the hermit’s chin. With Russell spouting blood and down for the count, a Tla’amin fisherman stepped in, who was even bigger than the logger. The fisherman had faced the same kind of grief that Russell had just gone through from the very same logger.

When the logger had initially attacked Russell, the fisherman had stepped outside to his pickup truck and grabbed a two by four. He returned to find Russell bowled over and bleeding, and the logger looming over him.

“Don’t touch him!” the fisherman shouted. “This stops now or you deal with me!”

The logger sized up the fisherman brandishing the two by four and thought better of any more brawling. Russell retreated back to the cove in Malaspina Inlet to recover from the vicious kick to the face. He realized later that he should have had stitches; the cut bled into his thick beard for days.

The fact that Russell had been in a bar fight completely captivated me when I was a kid in the 1980s. It was like something out of a Clint Eastwood movie, and Russell had the matted blood in his beard to prove it. As I entered my teen years, the hermit continued to be a backwoods mentor to me.

The hermit slowly drew me out of my insecure shell, convincing me that the world around me wasn’t going to bite. He taught me practicality in knots and knives, as well as ambition and idealism, intellectualism and philosophical thought, including his favourite: amor fati (love your fate).

Another one of the hermit’s mottos for Desolation Sound was: “There is always something to see.”

Whether it was a surfacing pod of orcas by day or infinite sparkling stars at night, it always seemed to be true.

Russell Letawsky graduated me from checkers to chess, teaching me that in chess, like life, sometimes you need to think three moves ahead. Russell would challenge the books I read, the music I listened to, and way I the way I perceived the world as a kid from the city.

Most of the tunes my family listened to didn’t venture too far into the musical alphabet: ABBA, the Beach Boys and Billy Joel.

Russell grew up a juvenile delinquent in Northern Alberta to the soundtrack of dirty rock ‘n’ roll. When I was a teenager, it was the hermit who introduced me to countless artists that I would scribble down on scraps of paper and track down once I got to the city: Chuck Berry, Wanda Jackson, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Guess Who, Pink Floyd and Supertramp.

The Hermit of Desolation Sound would set the hook of rock ‘n’ roll and counterculture so deeply within me that music would soon become my life, and it would be the driving force that would lead me far away from Desolation Sound for a long, long time.

But what happened to Russell Letawsky? You’ll read that story in the next chapter of Hermit of Desolation Sound.

Grant Lawrence is an award-winning author and radio personality who considers Powell River and Desolation Sound his second home. Hermit of Desolation Sound is currently airing as a weekly radio serial on North by Northwest, CBC Radio One in BC.