Previous chapter [“The beginning,” September 20]: The future Cougar Queen of Okeover Inlet and her family arrived via coastal steamship to her family’s homestead on an isolated isthmus of land in-between Penrose and Trevenen bays. There they built a cabin to live in, but it blew over in the first windstorm. They build a second cabin, but once the winter rains came, a river ran under it. They began to raise livestock, but their animals quickly became targets of the forest predators.

You would think the economic free fall of the 1930s wouldn’t impact families living in distant wilderness outposts in Canada, but the Great Depression hit hard. In the 1930s, there were dozens of children in the inlets of Desolation Sound, BC, but with so little money and so few jobs, malnutrition and starvation became a reality.

Hunger is difficult to imagine in a place teeming with ocean life, but in the early 1930s, three children were taken to the Powell River hospital suffering from starvation. Nancy Crowther herself wasn’t far behind.

One morning during the same bleak period, she was so weak and hungry that Nancy found she could no longer stand. Luckily, one of the family goats freshened with milk for the first time in days, and that milk managed to put preteen Nancy back on her feet.

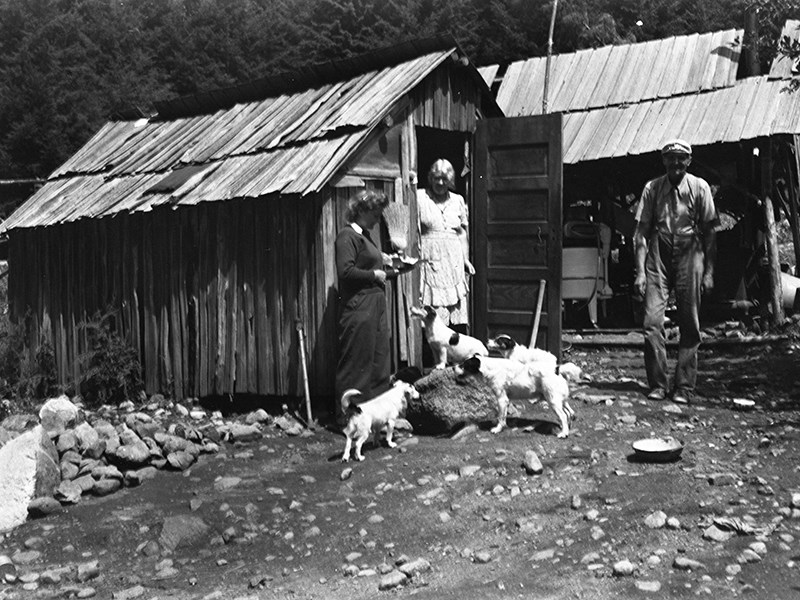

As the depression wore on, the Crowther family sold clams to get by, but once their shoes wore out on the rocky beaches, they couldn’t afford to buy new ones, so they wrapped cloth around their feet to protect them from the barnacles. When their store-bought clothes fell apart, they replaced them with garments made out of discarded flour sacks.

If life in Okeover Inlet wasn’t hard enough, Nancy’s father William began to have trouble with his eyesight, and the family feared their patriarch was going blind. Wild animals abounded, and Nancy’s father knew he had to teach his family how to shoot their only gun: an old, single shot .22 calibre rifle.

Besides their dogs, the gun was the only thing they had to keep the cougars, bears and wolves away from their goats and chickens, which were vital to their health and survival, especially during the depression.

In the late 1930s, one cougar had been repeatedly targeting the Crowther family’s livestock. The cougar had killed three of their beloved goats, one goat each month, returning each successive month to take another. Nancy’s mother had warned her: never turn your back to the woods. Cougars are silent and attack from behind. They are the ghosts of the forest.

Cougars had become such a problem with Sunshine Coast settlers and their livestock that the local government had placed a $5 bounty on cougar pelts, which greatly increased the incentive to kill them.

On a warm, late summer night in 1939, the Crowthers were enjoying an evening on the porch when the goats started bawling and their pack of dogs started howling. The cougar had returned.

Nancy, now in her late teens, grabbed their old rifle, which by this point was falling apart. It didn’t shoot straight, had a loose wooden stock, and wouldn’t eject cartridges after being fired. They had to force the cartridge out with a wire before loading it again.

That didn’t stop Nancy from rushing into the bush with the rickety gun. She followed the barking pack of dogs for over a kilometre through the woods, until she finally saw it in the soft light of the summer evening. Her dogs had treed a huge cougar.

It was a majestic and perfect creature. Perched in the limbs of a giant cedar, the cougar’s tail twitched like a house cat, its ears pressed back against its head, big eyes glaring. It let out a screech that made Nancy’s blood run cold.

Nancy Crowther then realized she was alone in the darkening forest but for her dogs, facing off against her first cougar with a gun that did not shoot straight.

A cougar hunter had told Nancy that if she ever had to shoot a cougar, she should tie up her dogs, but that night, she didn’t have any rope. Quickly, she took off her belt and tied up her biggest dog to a small tree. It was a strong, bellowing hound that was practically foaming at the mouth with excitement. Nancy couldn’t do anything about her several smaller dogs, all of which were in a frenzy at the base of the tree.

Nancy noticed she was shaking. She methodically laid down on the forest floor about 15 feet away from the cougar, calmed herself as much as she could, and carefully aimed the rifle. She knew the old gun shot high, and that she had to shoot for the cougar’s vertebrae, right in the neck, just as she had been told by the cougar hunter.

Nancy waited and waited until the cougar finally lifted its head. Nancy only had one bullet. She pulled the trigger. The cougar let out another screech and leapt to the ground. Nancy couldn’t be certain if she had hit the cougar. Then she lost sight of the wild cat among the salal bushes in the fading summer light.

And so there was young Nancy Crowther, unarmed but for an empty rifle, over a kilometre from home, with a potentially wounded cougar less than 20 feet away from her. What would you do? What did Nancy do? You’ll find out in the next chapter of the Cougar Lady Chronicles.

Grant Lawrence is an award-winning author and a CBC personality who considers Powell River and Desolation Sound his second home. Portions of the Cougar Lady Chronicles originally appeared in Lawrence ’s book Adventures in Solitude and on CBC Radio. Anyone with stories or photos they would like to share of Nancy Crowther are welcome to email [email protected].