A program designed to address the under-representation of aboriginal students in Canadian universities is expanding with a Powell River connection.

Since 2008 Verna J. Kirkness Education Foundation has worked to increase the number of First Nation, Metis and Inuit students graduating from science and engineering programs in Canada by offering high school students a unique opportunity. The foundation’s namesake, a member of the Fisher River Cree Nation, is a national leader in education and advocate for aboriginal education.

The program offers scholarships to grade 11 aboriginal students to spend a week in a research lab at the University of Manitoba (U of M). During their week on campus the students meet role models and mentors and experience the excitement of doing university level scientific research.

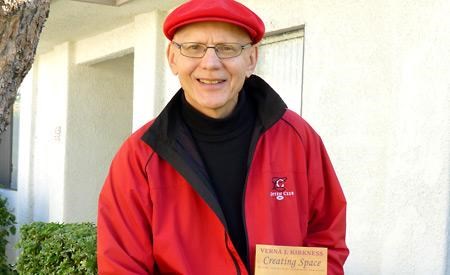

“It’s more than a university orientation,” said Ron Woznow, foundation chair. “They are going to live in residence, eat residence food, discover the campus. This is different than a university orientation—it’s an opportunity to excite them about research.”

Gerry Brach is a School District 47 counsellor and serves as the head teacher at Ahms Tah Ow School, which operates in partnership between the school district and Tla’amin (Sliammon) First Nation. The school gives high school students an opportunity to learn about Tla’amin language and culture.

Aboriginal students are about three times less likely than other Canadians to complete a degree, said Brach.

He estimates that while 70 per cent of aboriginal high school students say they plan to go to college or university, in actuality less than eight per cent complete a degree. He added that of those eight per cent a fraction are graduating with science or engineering degrees. “It’s probably one or two per cent—a very low number anyway,” he said.

Barriers for aboriginal students was a topic of discussion at a 2011 Queens University conference on indigenous issues in post-secondary education. In his address to the conference, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo recognized the legacy of residential schools.

“Education has been an instrument of oppression used against us, emphasizing the removal of our identities, the fracturing of our families and the elimination of our ways of communication, thinking and being,” said Atleo. “Our challenge today is to work together to...turn education from an instrument of oppression to a tool of liberation.”

The program has been embraced by faculty, staff and researchers at U of M.

Woznow hopes that as more aboriginal students study food science, community health improves as the connections between nutrition, food choices and health are strengthened.

“We were looking at the rates of diabetes and obesity on reserves in Canada—it’s epidemic,” he said.

Research topics that students have worked on include analyzing different water sources for bacteria concentration and learning how to improve the nutritional yield of various types of flours.

“If you had an engineering degree and you had the opportunity to return to help build a sewage treatment system and do things that would create fundamental change in the community, we believe there’s a much better chance you’d go and make it happen,” said Woznow. “It’s the same if you are a teacher or a health worker.”

The foundation approached the president of U of M because Woznow, an adjunct faculty member at the University of Guelph and executive for a research organization, had worked with U of M faculty and researchers previously and was impressed by the work being done in food and kinesiology research.

“I’ve always been a believer that you can change the world by working with young people and grandparents,” said Woznow.

The program is designed to create long-term connections between the students and their mentors, he added. Students receive a laptop computer as part of the scholarship, so they are able to stay in touch.

The foundation is funded by Canadian corporate donations from Canada Trust, Power Corporation of Canada and Merck & Co. as well as support from U of M. Woznow said that while it might not be particularly special for a foundation to have corporate sponsorship, what sets the organization apart is that the board members cover all administrative costs themselves.

“One hundred per cent of donations help get students to the University of Manitoba,” he said.

Now that the program and logistics are working well, said Woznow, the foundation board is looking to expand and Powell River figures heavily in their decision.

Woznow lived in Vancouver for 20 years before moving to Guelph and has a cabin south of Powell River on Hardy Island. He and his wife Susan O’Brien, an American from San Diego, decided last October to spend some time at their cabin and explore Powell River.

“This is where we want to live,” said Woznow, who has lived in eight Canadian cities. “It’s got a community spirit that’s just unparalleled—not to mention the physical beauty. I’ve never experienced the type of community spirit.”

He added that it did not take long before he and O’Brien started talking about how Powell River would be a great place for the foundation’s program. The foundation is currently talking with representatives from Vancouver Island University, the school district, Powell River Academy of Music and other organizations to create a similar kind of program but with a fine arts focus.

Brach said that five Powell River students have already applied for the next session over spring break at U of M and the foundation’s work has inspired him to try to develop similar mentorship opportunities.

“Five is an incredible number, but think if it were 25 or 35,” he added, saying the school districts are usually only able to send two students to the program each year.