Christmas dinner in British Columbia could look a little different this year as nearly two dozen farms across the province slaughter hundreds of thousands of birds in an attempt to contain the avian influenza virus.

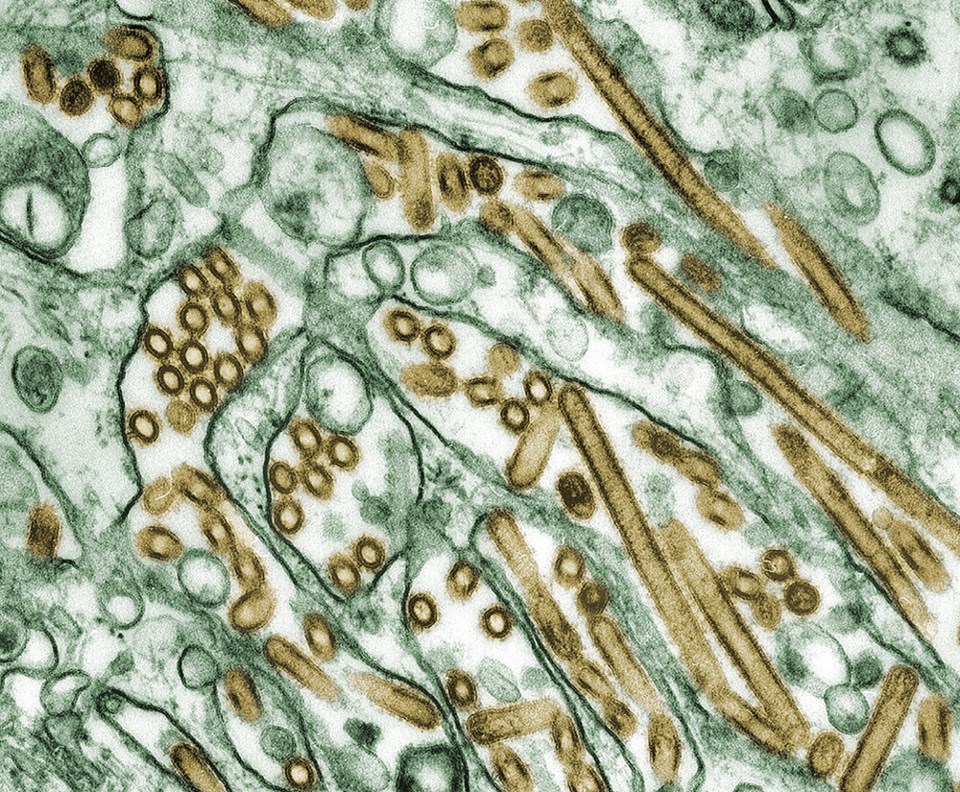

From the Interior, to the Fraser Valley and Vancouver Island, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has identified high-pathogenic strains (HPAI) of H5N1 — the most deadly variety of avian influenza or “bird flu”— in 42 B.C. flocks. As of Wednesday afternoon, 23 outbreaks were ongoing and 275,800 birds had been slaughtered in an effort to contain the pathogen.

The culled birds include broiler chickens, ducks and laying hens, among other specialty birds. But the most heavily affected poultry has been turkey, says Amanda Brittain, chief information officer for the BC Poultry Association, the group that helps coordinate the province’s four poultry and egg marketing boards during emergencies.

“The BC Turkey Marketing Board tells me that they’re looking to be 20 per cent short of how much they grow,” said Brittain. “Turkeys grow for 13 to 15 weeks, so there is no time to grow more before Christmas.”

H5N1 has been identified at over 220 locations across Canada and led to the culling of 3.7 million birds since the start of the latest epidemic.

The seven commercial Fraser Valley poultry farms hit with the virus since Nov. 16 have come under “intense disease pressure,” said B.C. Minister of Agriculture Lana Popham.

From the wild to the farm

The outbreaks in Chilliwack and Abbotsford come out of step with the seasonal migration of wild birds, which have been found to carry and pass on the virus to domestic flocks.

"The virus this year is different than we've ever seen in the past and it is behaving differently in both wild birds and domestic birds," said Brittain.

Scientists have isolated variants of the influenza virus in more than 100 wild bird species worldwide, from waterfowl like geese, swans, ducks and gulls to shoreline species like sandpipers, plovers and storks. Not all strains are deadly. In the same way that many humans pull through an annual bout of the flu, many strains of the avian varieties rarely cause more than the sniffles, lethargy or fever in birds.

High-pathogenic strains are different. When HPAIs enter a poultry farm, they often find the epidemiological equivalent of a refugee camp for birds, says Ronald Ydenberg, a professor of behavioural ecology and director of Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Wildlife Ecology.

“There are thousands of birds there. They're all immunologically naive. They haven't had time to evolve any resistance. And there's a fresh batch every six weeks,” he told Glacier Media last spring.

The viruses that cause avian flu can be shed through a bird’s saliva, feces and nasal secretions. If an infected animal sheds into a pond, near a bird feeder or in a cramped barn, it can easily pass on to another individual — whether wild or domestic.

This is where turkeys may be most vulnerable, says Brittain. Some are raised in open barns, where only partial walls and tarps protect the flocks from foul weather.

“In an open barn, it’s harder to prevent the migratory birds from getting in,” she said.

Avian flu in pets and humans

CFIA says there have been no cases of wild birds passing the virus to humans in Canada, but transmission from pet birds to humans is still a risk.

“Current science suggests that the risk of a human contracting avian influenza from a mammalian pet is very low,” notes the federal agency.

Owners are still encouraged to take appropriate precautions to protect their pets and themselves.

There’s always a potential for low-pathogenic avian flu viruses to evolve into highly pathogenic viruses. Such a novel virus could emerge with pandemic potential among the human population.

“H5N1 infection in humans can cause severe disease and has a high mortality rate,” states the WHO. “If the H5N1 virus were to change and become easily transmissible from person to person while retaining its capacity to cause severe disease, the consequences for public health could be very serious.”

Since highly pathogenic Asian bird flu strains emerged worldwide in the past two decades, many worried H5N1 would jump to people like the incredibly deadly Spanish Flu 100 years earlier, said Ydenberg.

But “it just didn’t happen,” he added.

Ydenberg says there is little evidence that this wave will be any different.

“I would say vigilance is required here. But certainly, if I were an average person, I would not worry about this very much.”

That level of certainty is unlikely to be matched at the grocer aisle this Christmas.

Brittain said that people should have no concern eating poultry or eggs. Finding a big bird and a good price is another question.

Since January, the wholesale prices of live turkeys in B.C. have climbed between 15 and 18 per cent depending on their size, according to Statistics Canada.

“We’re fine on chicken and eggs. But it is a concern with turkeys right now,” said Brittain.

“What I’m hearing is that avian influenza is making it very challenging for turkey farms and producers to meet demand in B.C. before Christmas. They have been hard hit.”

With files from the Canadian Press