Mars continues to brighten through November, from magnitude -1.2 up to magnitude -1.8 and its disc increases from 15” (arc-seconds) to its maximum of 17”. The first of the month at midnight sees it about 35 degrees above the eastern horizon and above and left of Betelgeuse in Orion. By the end of the month at about midnight, it will be about 65 degrees above the horizon to the SSE and above and to the right of Betelgeuse. Its motion is now clearly retrograde – to the west – and since we’re catching up to it and we’re also nearing the winter solstice when our north pole points away from the sun (and toward Mars), it looks much higher in the sky. It will reach its closest approach to Earth early on Nov. 30, although its actual opposition is six days later, since the orbit of Mars is more elliptical than our own.

Jupiter was at opposition in late September and is eye-grabbing all night long. My wife and I met a friend whilst dog-walking and she button-holed me to ask what that bright star or planet was that she could see each night. I told her it was Jupiter and she said she had thought so but someone else told her it was too bright and therefore must be Venus. I did point out, probably unnecessarily, that it would be hard to see an inner planet on the outside of Earth’s orbit. I’d guess she’ll be having another conversation with her friend on that subject shortly.

Saturn is well past its opposition in mid-August. I have tried a number of times to see Titan, its largest moon, with 15 x 70 binoculars but without success. At 40x in a telescope, it’s easy but not with the binocs. I’ll keep trying.

On a separate matter, but one that will be important very shortly after, Daylight Savings Time ends in the morning of Nov. 6; set your clocks back one hour because the truly big deal for November will be a twofer on the night of Nov. 7/8. Two minutes after midnight (hence the 8th) the moon contacts the penumbral shadow of the Earth and the eastern limb of the moon begins to see less and less of the sun. While there is a gradual darkening of that eastern limb, by about 1:09 a.m. it hits the umbral shadow and starts to enter total shade. By 2:16 the moon is in complete shadow. Mid-eclipse is around 3 a.m. on the 8th and the moon passes a little bit north of dead center through the umbral shadow. The moon can be almost invisible in a deep lunar eclipse, its only illumination comes from sunlight refracting through the Earth’s atmosphere and the colour can be anything from pale gray to pinky-gray to dark red.

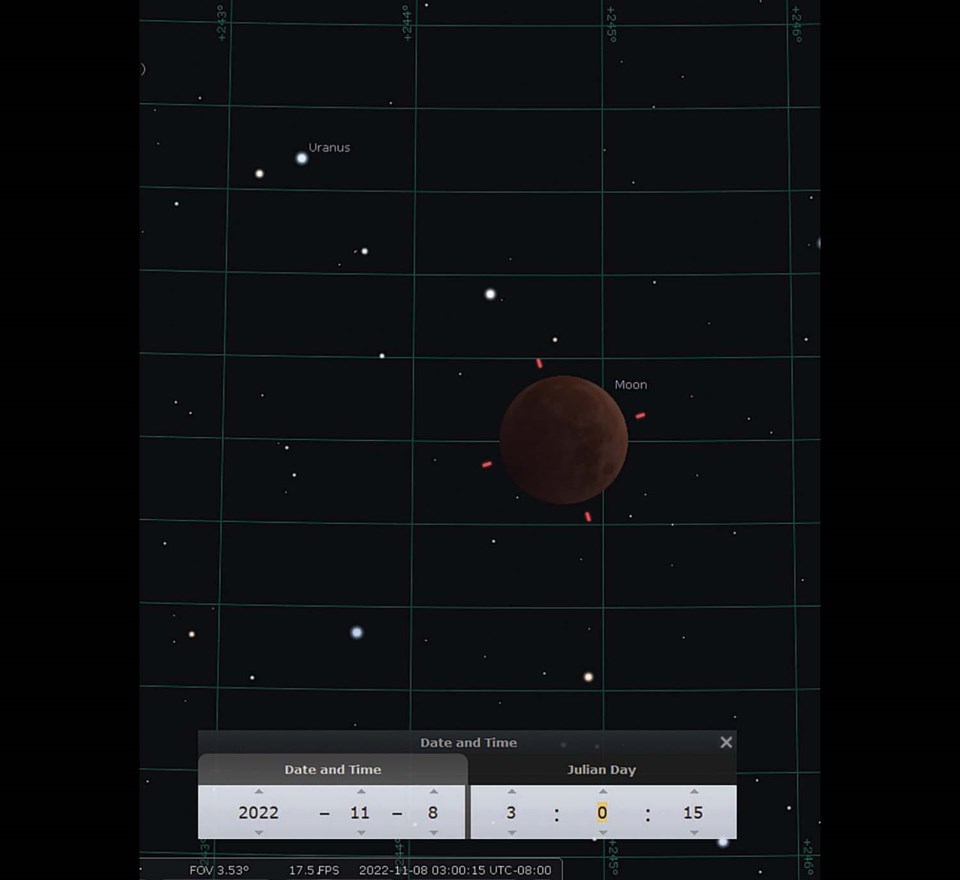

During this deep part of the eclipse, any good pair of binoculars ought to show a faint star about two or three moon diameters to the upper left at about the 10:30 position to the moon. If your eyesight is top-notch, it may be visible to the naked eye. This “star” may look a faint green colour and probably won’t twinkle as much as most stars; that’s because it’s the planet Uranus. It was pointed out to me at our last SCAC meeting in October that although as the moon comes out of the penumbral shadow, it passes very close to Uranus, the best time to see Uranus is when it isn’t washed out by the glare of a full moon. Good catch, Bruce! The screenshot accompanying this article is from Stellarium and shows what we should see at mid-eclipse – about 3 a.m. on Nov. 8.

As a matter of interest, Uranus was discovered March 13, 1781 by astronomer William Herschel, the first planetary discovery since Biblical times. According to Wikipedia, at the time the crowns of Great Britain and Hanover were united under King George II. William played the oboe in the regimental band of the Hanoverian Guards but after some military setbacks inflicted by the French, he was sent to safety in England after the death of his father.

To quote Wikipedia, “In addition to the oboe, he played the violin and harpsichord and later the organ, composed numerous musical works, including 24 symphonies and many concertos, as well as some church music. Six of his symphonies were recorded in April 2002 by the London Mozart Players.”

Herschel’s younger sister, Caroline, who joined him in England in 1772, was also somewhat talented. Besides accompanying him as soprano soloist in concerts, she joined him in his astronomical work, ground mirrors, worked as his observations recorder, discovered Messier 110 – a companion galaxy to the Andromeda galaxy – and discovered eight comets.

This makes all of us feel we’ve truly accomplished something remarkable in our lives, right? Does anyone reading this actually play the oboe? Know anyone who does? Found any planets lately? More on this remarkable pair can be found at: space.com/18704-who-discovered-uranus.html

The November club meeting open to the public will be Nov. 11 at the Sechelt Library at 7 p.m. The lecture topic will be posted at the Sunshine Coast Club website at sunshinecoastastronomy.wordpress.com/ .