Talk of an overland route linking Powell River and Vancouver, via Squamish and the Sea-to-Sky Highway, has been heard for as long as many can remember. Mention of the prospect is often met with skepticism if not outright ridicule that it may ever happen. However, with another spate of potentially damaging cutbacks to ferry service, the time may have come to ask when, not if, to start building.

For Lorne Craig, president of the Third Crossing Society, which advocates for the highway connection, the dialogue has now changed. “There are many questions yet to be answered and challenges to be overcome,” he said. “For one, the same dialogue continues from the government, an administration that seems to possess a decidedly terse disposition toward opening up the BC south coast to economic expansion. So far, in light of the deeply ingrained problems with maintaining ferry service here, it seems the decision makers have taken a hands off/let’s wait and see approach.”

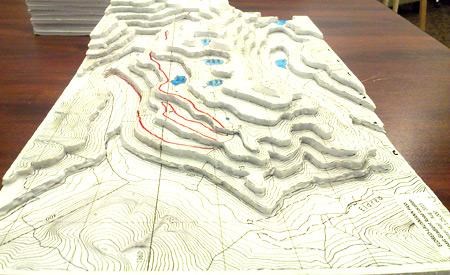

The topic comes and goes in the arena of public discourse, but behind the scenes the members of the society have been busy at work laying a foundation that may go a long way to bringing development for what Craig and his associates are calling The Glacier Trail. “Sometime in 2014, we will start seeking official approval to push the trail through what are mostly public lands running from the Goat Lake Main, over the Lausman Pass and down into the logging road network along Jervis Inlet,” Craig said. “It’s not a huge insurmountable distance...it’s only about 17 kilometres. Old logging roads already exist along most of its likely route.”

The Glacier Trail would benefit more than a dozen other communities in the Glacier corridor linking Campbell River and Comox to Powell River, Lillooet, Golden, Kamloops, Pemberton, Revelstoke, Salmon Arm, Sechelt, Squamish and, perhaps key to the plan—Victoria.

The society’s board of directors are pushing for approval from three regional districts, the province and the two first nations over whose lands the trail would pass. The overall plan would, if successful, incorporate the recreational plans within each of those districts and open up some of the most breathtaking scenic landscape and glacier formations in BC.

Whether or not a transportation route would link the Upper Sunshine Coast with the Lower Mainland is a question that has its roots in the very beginnings of economic expansion throughout the province. Like many areas of BC, especially in the southwest, the promise of a railway line punching through the Coast Mountains meant future prosperity. Corporations, industries and entire townships rose and fell on the promise of a railroad. Eventually, as the railway lines expanded in western Canada, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), Canadian National Railway, a Grand Trunk mainline, or a spur thereof, would run through an area to allow exploitation of a mine or forestry operation. Towns would spring up on the mere whispering of a railway coming through.

Sometimes a proposed railway never materialized. Early townships that were founded upon the notion are now little more than wood dust. The once industrious clearings where these young hopeful towns stood are now all but swallowed up by encroaching wilderness; Fir Valley just out of Winfield, and dozens of others just like it, are strung throughout BC.

In the late 1800s, the race was on to find a navigable overland route to the BC coast. There were several early attempts to punch a railroad into or near Powell River, but the ultimate question of whether or not a successful line would be completed was decided as early as the 1870s, well before Captain Israel Powell ever set foot on the shoreline here.

By mid-19th century, once a Hudson’s Bay Company fort was established at Victoria and the city of New Westminster was built, the Dominion government, via CPR endorsement and funding, seized upon the necessity of building its continental railroad routes into BC. By early in the 20th century, both the Grand Trunk and Canadian Northern railways joined in.

Enter the era of the railway surveyors in the west, a brand of quietly rugged men, legendary in their tenacity and perseverance, who were hired for good money to get the job done. The challenge they were tasked with was to find economical, navigable routes to push the transcontinental railways through the mountain passes in western Canada, thus opening the country to equitable trade. The surveyors were commissioned by the respective railways who were each vying for supremacy to survey specific stretches of passage.

A sense of urgency kept the fires lit under the men. Canadian railroad companies were neck and neck in the epic race against the US to punch through to the coast of BC in the case of Canada, and Oregon and California in the US. The first to cross would gain a decided advantage against its opponent.

,By the time CPR surveyor and public works minister, Sandford Fleming managed to punch a passage through the perilous Fraser Canyon, a handful of other railway companies and a small contingent of surveyors were competing against one another to open other areas of the BC coast. Where access to the south coast is concerned, of four original possibilities, attempts were made at three: Dean Inlet, Bute Inlet and Toba River at the head of Toba Inlet. Around the time of World War I, investigation of a possible route that would link Powell River with Squamish—what is now touted as the Third Crossing—was also considered.

Today, talk is centred around a road, rather than a railroad, but access remains the guiding factor. As coastal communities struggle to re-invent themselves in the face of the shifting economy, the apparent alternative is to entertain the notion that, lacking a viable mode of transportation, they will be left to simply die on the vine. With each stroke against the ferry service people are now asking serious questions, asserting that a mid-province corridor is a workable solution.

This is the first of three articles exploring the feasibility of an overland access from Powell River via Squamish to Vancouver, with more to come from the society’s initiatives and on the intriguing and sometimes tragic history of the search to open up the BC coast.