Douglas Ladret, a two-time Olympic athlete competing in pairs figure skating, is about to return to the place it all began. Ladret and nine other inductees will be welcomed into the Powell River Sports Hall of Fame later this spring.

He started skating when his big brother Greg, about 13 at the time, began skating lessons to play hockey. When he was four years old, his family would walk the three or so blocks to the Willingdon Arena to practice. His parents noticed the young Ladret had a natural balance on the ice, so they arranged for a coach, and although there was a bit of turnover in skating coaches, he grew to like it.

His youth was filled with hockey, baseball and rugby. Although skating was almost always present, it would never compare to his real passion, music.

“Skating was just kind of a thing I did,” he said. “It wasn’t an aspiration; it was just an activity.”

When Douglas was about 10, he watched Greg and his ice dancing partner, who were both from Powell River, move to Vancouver to train in figure skating more seriously. It was about this time the 1972 Sapporo Olympics were happening. Douglas said he remembered the opening ceremony, the torchbearer running up to light the torch.

“That was kind of the moment it hit, that I wanted to do that,” he added. “I wanted to be there.”

Douglas also moved to Vancouver, where he would have better access to coaching. He travelled to regional events and made his way to national championships by the time he was 13.

Love of music

Throughout high school, he was heavily involved in musical theatre, band and jazz choir. He said skating at that time wasn’t going well, so it took a back seat to his real passion.

In grade 12, he played in a band at weddings and nightclubs and worked at a catering company to pay for his skating.

“[Music] was my real passion throughout. I was just good at skating, which is kind of a weird thing because some people say that when you lose your passion is when you retire,” explained Douglas. “Well, it wasn’t a passion. I was just good at it, so I kept going. But then, when I wasn’t good at it for a while, I chose to follow my passion, that was music.”

When he was 19, he nearly dropped out, thinking he was too old for the sport. He debated going to college for music when an old high school teacher encouraged him to stick with skating while he still could.

Serendipitously, this is when he watched Lyndon Johnston, at 19 years old, win the junior level national championships in singles.

“He was doing the exact same jumps that I could do,” said Douglas. “He was the same size, maybe an inch taller than me, and I’m thinking, ‘Why am I too old, but he’s winning the national titles in junior.’ So that kind of sparked something.”

The spark

Douglas immediately started training under Johnston’s coach, Kerry Leitch.

“I’ve never been so tired in my life; I never trained like that in my life, ever before,” he said. “But I’ve never been put through a training protocol like there was under Mr. Leitch.”

Under Leitch’s coaching, 1984 was a big year. He skated his first international competition and was paired up with Christine Hough, who would be there with him through some of his most significant skating moments yet to come.

He and Hough just clicked, had great chemistry and quickly became one of the best throwing teams in the world.

In 1986, the infamous accident happened. Ladret’s skate got stuck in a rut during a throw, and they both tumbled to the ice. Ladret tried to pull Hough forward while he fell backwards; that’s when his head hit the ice.

He didn’t think much of it besides the feeling of his ear clogging up. But after inspection, the team doctor sent him to Hamilton General Hospital. Tests revealed he fractured his skull.

“I can hear [my coach] in the hallway with the doctor saying, ‘we’ve got a competition in Moscow in a couple of weeks, when can he get back on the ice?’ and the doctor said, ‘after the night, he can think about skating after that. He’ll have to make it through the night first.’”

This was the first time he’d seen his coach scared. Usually, Leitch was the “there's only one way off the ice, you better be bleeding or dead” type.

For Douglas, the accident was no big deal. He came from a family of fishermen and grew up hearing stories of boats running up on rocks, exploding and catching on fire out at sea.

“For me, it was like I just cracked my skull. At least I’m not stuck at sea.”

Five weeks later, he was back on the ice, but this time wearing a hockey helmet.

The pair played it safe at sectional championships and qualified for nationals, where they went full throttle, Douglas still wearing his hockey helmet for protection.

“What we thought would be career-ending, we ended up third,” he said, “which qualified us for the world championships for the first time.”

Going for gold

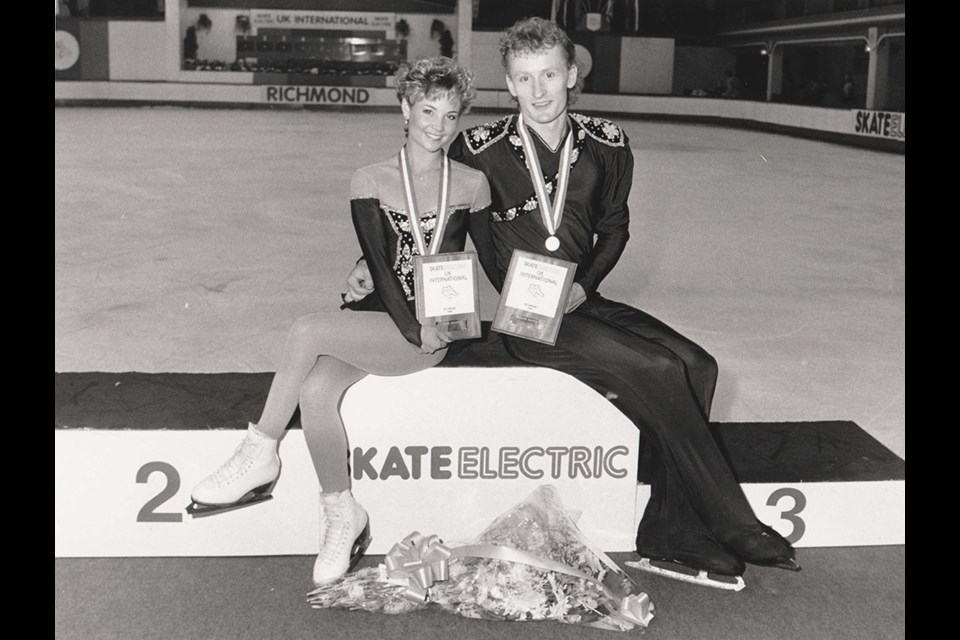

They would go on to win gold at the 1987 Skate Canada International and 1988 Canadian Championships.

Then came the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, where the pair placed eighth. A special moment was skating onto the ice in the Saddledome in front of 22,000 people.

“I have never been in front of that many people before in my life, other than the opening ceremony,” he said.

They landed an incredible throw, and all 22,000 people cheered and screamed.

“I got scared. I got absolutely scared. It was so loud. It scared me to death.”

Between the two Olympic competitions, there were some highs and lows. The team won the bronze medal at the 1989 NHK Trophy, silver at the 1990 Nations Cup, and gold at the 1990 Skate Electric.

This was before being sent to the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville, France, where Hough and Ladret finished ninth. After their long program, they received a standing ovation from the referee, something they’re not allowed to do.

“He just said: ‘You deserved it, for your career,’ like wow, that’s pretty cool.”

Post Olympics

After the Olympics, Douglas went on to perform with Stars on Ice from 1992 to 1997, where he was once again able to explore his love of music, but this time with a figure skating twist.

“I started to experiment with adding music on top of music. Back then, vocals were not allowed in skating competitions, so I started to record musical versions of songs that people would want to skate to. So I had the synthesizers and programmers and everything.”

Combining his love for music and the knowledge of what skaters liked to skate to, he became pretty good at it and produced many edits for the show.

Later, he and his wife opened a practice facility and coached some international skaters.

“The fun thing was getting back to Canada, coaching at Skate Canada, in Quebec City, Halifax and Victoria,” said Douglas. “It came full circle that way. There are a lot of places where I got to coach.

He said being inducted into the Powell River Sports Hall of Fame is a huge honour.

“I was shocked. It’s been so long since I’ve done anything about skating; I tried to stay in the background as a coach,” he added. “Starting out at Willingdon Area by the beach and ending up in the mountains of Colorado. Being able to come back for that it’s pretty cool.”

Douglas lives in Colorado with his wife and son.