Here’s the optimistic version: If they’re going to unveil a permanent fix for the Malahat anyway, it would be nuts to chuck a bucket of money at an emergency-detour route.

But that’s a big if.

A much-anticipated study of potential Malahat detours was made public Monday, with the provincial government deciding to do … nothing. Or, at least, nothing other than focus on improving the safety of the existing highway.

Boiled down, the study argues that the Malahat isn’t cut off often enough to justify the cost and risk to the environment associated with building an emergency route to be used during long-term closures.

The question now is what we will see this spring, when the government is to unveil a much larger transportation plan for southern Vancouver Island.

“I hope it’s a good sign,” Langford Mayor Stew Young said of the decision not to go ahead with a detour route. An expensive stopgap doesn’t make sense if a big-picture solution is on the way — though it better come with funding attached, he added.

“If they get another study that sits on a shelf … that will be a problem for any government.”

Patience with congestion and periodic Trans-Canada closures is already in short supply. When the highway is severed, the only existing alternatives are no real alternative at all. The Mill Bay ferry can only handle 22 cars per trip, while the Pacific Marine Circle Route via Port Renfrew and Cowichan Lake takes a good 3 1/2 hours and isn’t built for heavy traffic.

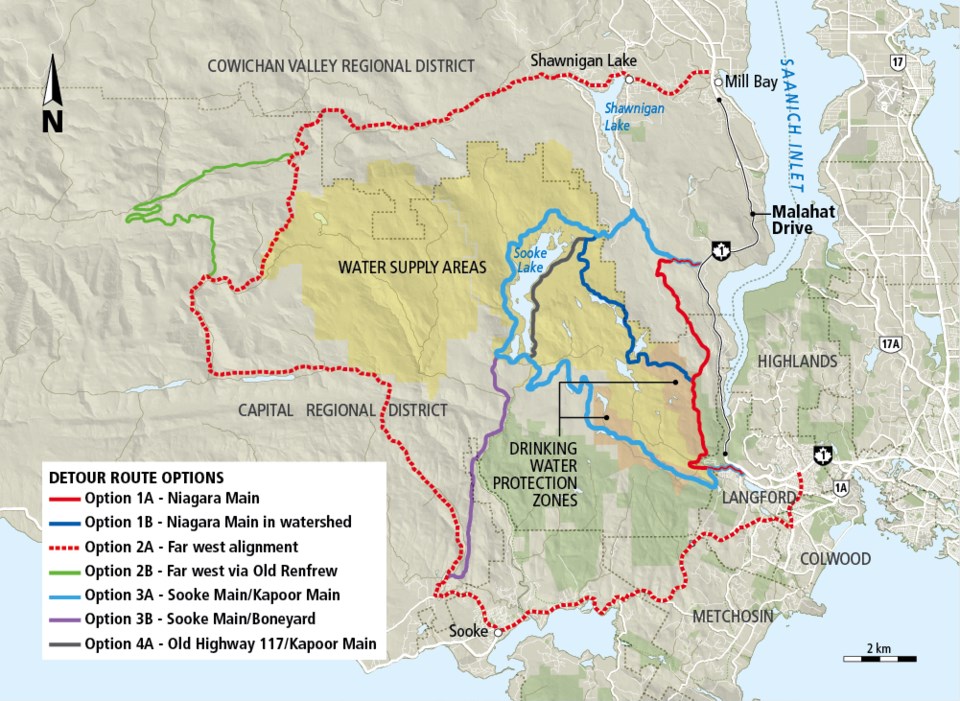

The consultants who wrote the 155-page report weighed seven emergency-route options, five of which they almost immediately ditched as being too costly, of too little benefit, or posing too great a threat to the region’s drinking-water supply.

That left two, including one that also seemed pie-in-the-sky: a 104-kilometre route that would take traffic west of the watershed and cost $180 million to build — twice as much as the McKenzie Interchange project. “That’s a lot of money for a once-a-year route that you hope not to use,” noted CRD chair Colin Plant.

That left the most obvious alternative, gussying up the all-but-abandoned Niagara Main service road through the Sooke Hills west of the existing highway. Only people working on the CRD water system can use it now. At 20.3 kilometres, it would be the shortest of all options. The cheapest, too, though $30 million is hardly chump change.

Approving the Niagara option would also have triggered one of the biggest enviro-political snarlfests to hit Vancouver Island since the Clayoquot protests of a quarter century ago.

As soon as the study was announced in January, environmental groups rallied and the Capital Regional District board, the CRD parks committee and the Regional Water Supply Commission all vowed to fight any route through the watershed or parks.

The Niagara Main bisects Sooke Hills Regional Park and runs along the edge of Goldstream Provincial Park. It skirts, but does not cut into, the water supply area, though there would be a conflict with a water-disinfection area. Upgrading the road would mean crossing as many as 29 streams, including the fish-bearing Goldstream River. The report cited the risk of wildfires.

“For the number of times we have a full closure, it doesn’t make sense to put that amount of money into something that would be contentious anyway,” says Transportation Minister Claire Trevena.

According to the report, the Malahat isn’t severed as often as we think. Between 2009 and 2018, the 12.8-kilometre stretch of highway between Shawnigan Lake Road and West Shore Parkway endured 40 closures of half an hour or more. On 11 occasions, traffic was cut in both directions for longer than 2.5 hours. That’s one big shutdown a year. To drivers who miss important appointments, it feels like more.

“I completely understand the frustration,” says Trevena, a frequent commuter between the capital and her home in Campbell River. She spoke of current work near the Leigh Road interchange, and of the possibility of extending median barriers.

She also spoke of increasing police presence on the highway, something Chris Foord, the vice-chairman of the CRD traffic safety commission, argued would greatly improve Malahat safety. (Note the 19 cars impounded for excessive speeding a couple of Sundays ago.)

Foord and Plant also pitched, again, the idea of mounting interval cameras to keep a leash on speeders, though Trevena quickly discounted that idea. “It’s not something we would be looking at at all,” she said.

OK, then what will they do? Foord fears the prospect of a speed demon colliding with one of the many fuel trucks that trundle over the Malahat.

He also wonders what the government will come up with as a big-picture solution this spring. As it is, the population at either end of the Malahat keeps growing. Think of the South Island as an hourglass, he says: “The bulbs at either end are growing, but the constriction point in the middle isn’t changing at all.”