It’s often the case that movies based on true stories offer a glimpse of the real-life characters at the end. In “The Mauritanian,” the story of former Guantanamo Bay detainee Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s 14 years behind bars, that real-life footage is the most engaging part of the film.

That’s not entirely the fault of the filmmakers, who do an earnest and thoughtful if less than totally absorbing job of telling Slahi’s story based on the

It’s just that nothing can beat this intimate view of the real man, smiling and singing joyfully to Bob Dylan, no less. One wonders how he even managed to stay sane, let alone joyful, after 14 years at Guantanamo without being formally charged or tried. And in conditions that included a brutal stretch of torture: severe cold, sexual humiliation, sleep deprivation, a mock drowning, waterboarding, and threats to imprison his own mother at Guantanamo.

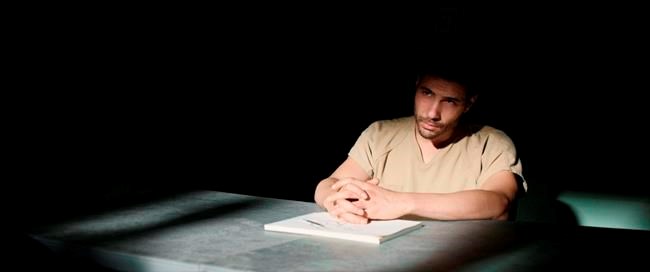

Luckily, “The Mauritanian,” directed by Kevin Macdonald, gets one thing very right: Tahar Rahim’s masterful central performance. The French actor achieves something his big-name costars — Jodie Foster, Benedict Cumberbatch and Shailene Woodley — do not, presenting a multi-layered, subtly shaded and deeply moving portrayal that proves hard to forget. Rahim deserves the awards buzz he’s getting; he also deserves more big roles, and soon.

Macdonald is known for documentaries (the Oscar-winning “One Day in September”) as well as features (“The Last King of Scotland”), and “The Mauritanian” has a quasi-documentary feel at times. Partly that’s because there’s a lot of dry information to get across here, namely the ins and outs of Slahi’s legal case. The film tries to achieve this by juxtaposing the stories of

Both Foster, in her brittle, crusty portrayal of Hollander, and Cumberbatch, sporting a southern drawl as a devoted military man with a conscience, are welcome presences in any movie. But the script here really doesn’t give them a lot to work with — we learn almost nothing about them as people outside the case. With actors of this

Rahim, though, has plenty of room to shine. The actor finds a way to infuse almost every scene with

Four years later in Albuquerque, lawyer Hollander is approached to use her security clearance to help find Slahi, on behalf of his desperate family. She has no idea of his innocence or guilt, but asks: “Since when did we start locking people up without a trial in this country?” She enlists a junior colleague, Teri Duncan, to help (Woodley, underused.)

Meanwhile we meet Couch (Cumberbatch, also a producer here), who’s tapped by superiors to lead the prosecution. They know he has skin in the game: his good buddy was a pilot on one of the planes that hit the World Trade Center. He asks: “When do we start?” It’s made clear that the goal is the death penalty.

The film tracks these two as they pursue their cases, each stymied by government restrictions on information. Hollander receives cartons of fully redacted documents; Couch seeks crucial details about interrogations. For each, the ultimate discovery of the torture Slahi went through will change the dynamics of the case.

But the most accessible scenes feature Slahi himself, whether they involve the dreaded interrogations or the prisoner’s basic efforts at making a friend at Guantanamo, a French detainee he speaks to through a green mesh fence, and who dubs him “The Mauritanian.”

The film has the rhythm of a legal thriller heading toward a dramatic courtroom trial. The true climax is hardly that climactic: Slahi testifies by video at his habeas corpus hearing. He learns by mail that he’s won.

He whoops with joy. He’s going home.

And then, the closing credits tell us, he remains imprisoned at Guantanamo for seven more years.

“The Mauritanian,” an STX Films release in

___

MPAA definition of R: Restricted. Under 17 requires parent or adult guardian.

Jocelyn Noveck, The Associated Press