It all quickly caught up with Kyle Scott after getting home from Afghanistan.

Slipping back into civilian life wasn’t easy after two tours in the war-torn country, considering all that he had seen and done over there.

Now 41, Scott had been part of harrowing firefights with the Taliban, including a 24-hour battle on May 17, 2006, that claimed the life of Capt. Nichola Goddard — the first Canadian woman soldier killed in combat. He watched fellow soldiers and the enemy torn up by bullets and shrapnel, took fire and gave it back.

Every day “was like walking on a razor’s edge,” said Scott. “But at the time, you’re just doing your job, you know? You’re doing what you’re trained to do.

“Getting home was different.”

After seven and a half years with 1 Combat Engineer Regiment — including that last bloody tour in Kandahar, where they roamed the province hunting the Taliban and searching for lethal improvised explosive devices — the gunner assigned to a LAV armoured vehicle had reached a dark space.

Experts call it post-traumatic stress disorder.

“They used to call it shell shock,” said Scott, who is sure his great grandfather, a First World War veteran who was wounded in the Battle of the Somme in 1916, also had it.

“They just called it something different and they dealt with it differently,” says Scott, who was medically discharged in 2008 for sustaining “multiple injuries.”

He “spiralled” after getting home to Whitecourt, Alta., started drinking heavily and arguing with friends and family. “I just couldn’t shut it off — I couldn’t de-escalate,” said Scott. “I was always the guy who did his duty, the guy who always made light of things.

“But I just wasn’t that guy anymore.”

A turning point came when he went to the Whitecourt cemetery, where he would visit the grave of Cole Bartsch, a friend who was one of five Canadians killed by a roadside bomb in Kandahar. Bartsch was 22, a few years younger than Scott.

“I used to go talk to him in the cemetery, and vent I guess,” said Scott. “It just felt like a safe space when nothing else [made sense] at the time.”

On his visits to the cemetery, he started to notice the poor state of other veterans’ graves, something that didn’t sit well with him.

So Scott embarked a new mission — one that would become his “life-saving” therapy: to provide proper grave markers for those who served in Canada’s military.

Through the Last Post Fund, which is administered by Veterans Affairs Canada and makes funds available for military grave markers for all veterans whose remains are in unmarked graves, Scott has been able to research soldiers and erect more than 1,300 markers in cemeteries across Canada over the past decade.

Victoria’s historic Ross Bay Cemetery has been a major benefactor. The leafy, seaside cemetery has been one of Scott’s favourite sites to honour veterans because his mother, who emigrated to Victoria with her family from Ireland in 1957, grew up a block from Ross Bay, which he spent many of his childhood summers and Christmases roaming.

To date, he’s found the names of 290 veterans who were buried in Ross Bay — many of them in unmarked graves in empty grassy areas. Each new grave maker costs about $2,000.

As of this week, about 140 new military markers have been installed in Ross Bay, with other stones in the process of being manufactured and readied for installation.

Veterans buried in the graveyard served in conflicts dating back to Confederation and even earlier, from the rebellion in India from 1857-1859 to the Fenian Raids in the 1860s and 1870s — incursions by a U.S.-based Irish republican organization on targets in Canada — and the First and Second World Wars.

Many returned to Victoria from these conflicts to live out their lives, but were never formally recognized for their service with military markers.

Scott has personally raised the money for other markers for veterans whose service fell outside the dates set out by the Last Post Fund, which is intended to provide funding for grave markers for veterans who served post-Confederation. These include members of British Royal Engineers, who came to B.C. in 1858 to build the colony, and some veterans of the Crimean War.

In researching veterans for the project, Scott connected with local historians like Sheryl Walker and husband-and-wife duo Betty Andersen and Dan McLeod, who took photos of grave sites in Ross Bay and investigated the plots — and sometimes researched the veterans’ military service.

Scott said Andersen and McLeod have done “much of the heavy lifting” in finding information through Find a Grave, a database of cemeteries and those buried. The site is owned by Ancestry, but is free to the public to search online.

Walker, who runs a Facebook page called Ross Bay Cemetery — Stories Beyond the Graves in Victoria, has been researching the cemetery since 1973. The cemetery contains more than 28,000 graves, including hundreds without markings.

She spends hours in the provincial and city archives finding out who many of the dead actually were, and said connecting with Scott in his mission to identify military personnel has been rewarding.

Since Scott’s project began, she said, “The military stones have been popping up on the south end of Ross Bay like flowers. Where there was a grass field with unmarked graves, there are reminders now of who these people were.”

“It’s so satisfying to put the pieces of the puzzle together. Most of the time, the families are all gone, but every once in a while you will hear from a descendant, and they’re thrilled they’ve made the connection.”

A sense of closure

It’s difficult to know all of the backstories of every solider who came home from war, though Scott’s own experiences tell him it was likely never easy making the adjustment back to civilian life.

Some soldiers buried in Ross Bay died paupers, others were vilified for their race or simply took their personal horrors of war to the grave.

“You don’t realize how privileged you are until you leave this country,” said Scott. “In war zones, there’s only so much training can do for you, and it does little to prepare you to come back.”

After a weeklong “decompression session” in Cyprus before returning home, Scott and members of his regiment were called to Rideau Hall in Ottawa, where he received a Mention in Dispatches for actions in Helmand Province of Afghanistan.

There, Scott’s armoured vehicle and others were called to rescue a British outfit in a community hall running low on water and ammunition and surrounded by Taliban. A fierce battle ensued, with both sides fighting for access to a bridge into the town. Accompanied by Afghan police forces, Scott found himself killing Taliban and helping the fallen, including a 15-year-old boy recruited by local police who fell wounded, blood gushing, after a Taliban bullet tore through his lungs.

“He’s looking at me, gasping for air and I’m shooting back and trying to figure out what to do,” said Scott, who used some basic medical training he’d received to do a battlefield chest decompression with the help of a medic using 15-inch needles.

The boy was later taken out by a British helicopter and Scott never knew if he survived.

He lives with those memories — walking though villages not knowing if he’d be shot, travelling in his LAV worried it could hit an IED and blow up on some desolate highway.

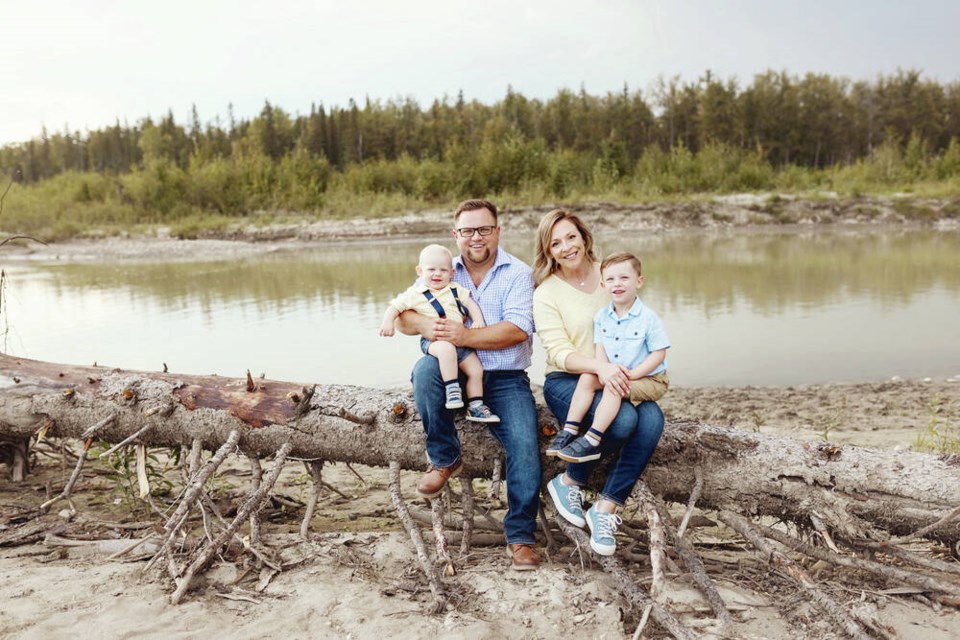

Since his discharge from the army, Scott has worked with ATCO as a journeyman gas fitter. He credits the support of his wife, Koren, and the Last Post Fund for helping him to find that “happy place.”

His sons, Declan, 5, and Niall, 2, are also helping.

“I am often walking them through cemeteries explaining who these people were and why they matter,” said Scott. “And my wife is all but an accidental expert in the field of markers and Canadian military history now. She has seen more graveyards then most, in Canada and across Europe … even on our honeymoon.”

As the descendant of generations of veterans, he says, the gravestone project feels like his duty.

“It also gives me a great sense of closure on my own issues that I brought home from my war. It makes me feel as though I am still serving in a sense. Something I miss dearly.”

Scott hasn’t had a chance to visit Ross Bay, first due to the pandemic and lately because of work and family commitments, but he’s continuing the work in Victoria and in other cemeteries.

“Veterans once forgotten are no longer — because we’re fulfilling the one promise we made them so long ago: Lest we forget,” he said. “I am so incredibly proud of this work and will continue on with this mission as long as I have the time and energy. I feel we owe it to them.”

A grave-marking tradition

Kerry Mann takes special care when he rolls a granite war-grave marker into the sand-blasting booth at Mortimer’s Monumental Works on Kings Road.

Moritmer’s is one of Greater Victoria’s most enduring businesses, established by Scottish immigrant John Mortimer in 1877, and responsible for many of the markers in Ross Bay.

Like his father, Ken, before him, Kerry Mann uses a steady hand to sandblast the name, regiment, emblems and dates of service and death into the stone.

Each of the slabs is quarried in Vermont, just over the Quebec border, in what is considered the finest and deepest deposits of light barre grey granite in the world, known for its fine grain, even texture and weather resistance — and the standard Veterans Affairs Canada markers.

Each of the upright stones is 39 inches high, 15 inches wide and three inches thick, with a slightly rounded top.

Mann makes a thick, rubberized print of each marker’s information, lays it over the stone and sandblasts the letters and emblems (usually a Latin cross, but also maple leafs, regimental emblems or cultural or religious references like a Star of David or Indigenous and Métis symbols) to a certain depth. The depth is critical to legibility, as no paints are applied to bring out the lettering.

“It’s work I’ve always enjoyed doing,” said Mann. “These are people that fought for our country and the things we believe it, so it’s an honour.”

Mann said he’s always amazed by how young some of the soldiers were. “Some of these guys were 16 or 17 years old when they went off to war. You can’t imagine a kid doing that today.”

Mortimer’s has had contracts with Veterans Affairs and the Commonwealth Graves Commission to install news stones and replace damaged ones across the province for the past 40 years, installing “many thousands” of the markers, said Mann.

New orders usually come in through the Last Post Fund, and there are calls for maintenance or replacements after tours of cemeteries by local members of the war graves commission.

The markers are installed in cities and small towns in every corner of the province — 500 in one Vancouver cemetery alone last year.

In 2017, he took a marker to Morpheus Island Cemetery, about a 10-minute boat ride off Tofino. The little cemetery with 25 graves in a clearing amid towering cedars and fir served the community before the roads were built. Three First World War veterans were in the graveyard, including Sapper Francis Robert Burnett Garrard, who died Oct. 25, 1919, and whose grave needed a new marker.

Mann and an employee for the district loaded the 200-pound granite marker and 250-pound concrete base, along with mortar and tools, into a 12-foot aluminum boat — sinking it to within a few inches of the gunnels and fighting a major current.

They landed on Morpheus and then carried and dragged the heavy marker and materials several hundred metres uphill on a narrow path over rocks and tree roots to the small clearing.

It was an all-day job, but satisfying, said Mann, because Garrard had the marker he so richly deserved for his sacrifice.

Mann said this Remembrance Day, people should visit Ross Bay to see the work that Kyle Scott has done to commemorate the forgotten military servicemen.

“It’s amazing the number that Kyle has found,” said Mann. “It’s a wonderful thing he’s done, because these people should be remembered.”