by Kyle Wells [email protected] You can learn a great deal from a 40-minute conversation with a few clients at Powell River Community Resource Centre (CRC).

You learn that people sleep in the sheltered area by the entrance to Powell River Public Library. You learn that people sleep on the beach during summer, in the woods behind the RCMP station and Powell River Historical Museum and Archives. You learn that many people in town dumpster dive for food and that some grocery stores lock their dumpsters to prevent this, an act considered by some to be cruel. You learn about the level of addiction in town.

Most of all you learn that there are a lot of decent, normal, easy-to-talk-to people who are struggling to keep their lives together.

Kelly Reid, 26, came to Powell River from Vancouver at the age of 14. Since then she has divided her time between the two places. She has been homeless or nearly homeless off and on for the past five years. She loves Powell River for its scenery and its small town comfort, but becomes frustrated with the lack of services available and inevitably ends up back in Vancouver.

“I love it here. It’s beautiful. It’s small and it’s not busy...it’s more laid back,” said Reid. “But I just can’t stand the homelessness part of it all and the issues. It’s brutal out here.”

Marie Major, 24, mother of a 19-month-old daughter, lives on income assistance that provides her with barely enough to support her and her daughter and keep them housed. Major grew up in Powell River and although she has never been homeless she has been on the edge for most of her life. She is currently living with her mother because neither can afford housing on their own.

“So it’s okay right now but we still struggle,” said Major. “It’s not as bad as some people.”

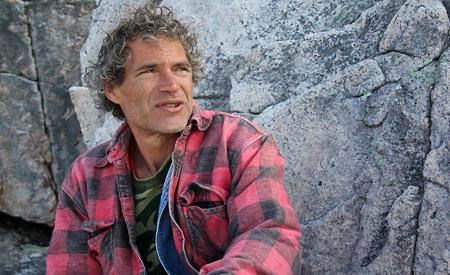

Eric de Beaupré moved to Powell River at the age of 21. He has never been happy working for others and is also independent in spirit, preferring to be his own boss. He is a common sight south of town, often seen walking with his enormous goat Echo or driving his vegetable-oil-fueled car. He refers to himself as “Supertramp” and spends much of his time performing smalls acts of kindness, such as cleaning up the recent graffiti sprayed on the bluffs at Dinner Rock.

He also fights with issues of anxiety and has been on disability for the last 10 years, living in a trailer south of town. He raised a child while living in a bus, eating at soup kitchens and living on income assistance, which eventually turned into disability assistance.

De Beaupré depends largely on the food given out by the CRC and other agencies. He said it’s not uncommon for him to eat an entire loaf of bread as a meal, or live off a large bag of popcorn for a day or two, whatever he can get from food banks or at the CRC. He survives but it isn’t easy.

“I kind of like having my bills paid, that kind of keeps the stress down,” said De Beaupré, “but it’s the food, I just know I don’t eat properly.”

On July 21, 2011 Powell River based Alof!i Consultancy presented the Powell River Homelessness Partnering Strategy Final Report to City of Powell River mayor and council at the committee-of-the-whole meeting. The city contracted Alof!i to put together the report with federal funding from Human Resources and Skills Development Canada for the purpose of bringing together a list of available services and developing future approaches to the issue of homelessness.

Research for the report consisted of a series of meetings with local service providers, research of background information on homelessness in Canada and committee meetings to discuss progress and approaches. The research also included interviews with people in Powell River who are homeless, or nearly homeless, people like Reid, Major and De Beaupré.

Homelessness is not easy to see in Powell River. You don’t often see people sleeping in doorways or on park benches. There are few people pushing shopping carts filled with cans or scrap metal. It’s a rare occasion to be asked for change. The main difference between urban and rural homelessness can be found in the term “hidden homeless.” This sums up the state of a person who is homeless in Powell River: unseen, unknown.

Rural homelessness is hidden because those living in it are not sleeping on the street, are not begging for change. They sleep on friends’ couches. They live in near squalor on disability or income assistance. They build or inhabit temporary shelters in the bush. They camp on crown land or find abandoned cabins. They find shelter anywhere they can.

So how many homeless people are there in Powell River? In a 2007/2008 housing assessment, also conducted by Alof!i, seven per cent of respondents could be defined as “absolute or hidden homeless” and a further nine per cent as “relative homeless,” meaning they spend over 70 per cent of their income on housing. In 2009, 8.5 per cent of people in Powell River were living on income assistance benefits.

In an area with a population of around 20,000, the final report estimates that more than 250 people are homeless and about 275 others are nearly homeless, often one missed paycheque away.

A lack of services, inadequate access to affordable housing and indifference or a lack of knowledge on the part of the public are all barriers to those struggling to rise above homelessness and are all topics tackled by the report.

Over the next three issues the Peak will look further at these and other topics in a series of articles on hidden homelessness in Powell River.